‘Highly toxic’ hemlock widespread in Upper Midwest

Poisonous invasive spreading through the region

UPPER MIDWEST – The toxic plant that killed Socrates thousands of years ago is becoming more prevalent in the Midwest. Poison hemlock is an invasive biennial plant that has tall, smooth stems with fern-like leaves and clustered small white flowers.

Hemlock can grow up to eight feet tall – and, according to Meaghan Anderson, an Iowa State University Extension and Outreach field agronomist, the plant is becoming more widespread due to several factors.

Those factors include unintentional movement of seeds from one place to another by floods, mowing equipment and animals. Hikers inadvertently transport seeds on their shoes or clothing.

Changing ecology could also be contributing to spread. For example, Anderson said tree loss resulting from derecho winds, as in parts of Eastern Iowa in 2020 (and more recently across southern Minnesota), make room for the plant. Cedar Rapids, for example, estimates it lost about 65% of the overall tree canopy that existed before the 2020 derecho flattened trees with hurricane-force winds.

“The loss of so many trees and opening of canopies has likely allowed for many weedy species to gain a foothold in areas they were not in the past,” Anderson said.

Since the plant was first introduced to the U.S. in the 1800s, hemlock has made its way into every state, except Hawaii.

Scott Marsh, an agricultural weeds and seed specialist with the Kansas Department of Agriculture, said though the plant is widespread across the country, it’s generally more common in central parts of the United States. He said it is slightly less abundant in the southeast and northeast parts of the country.

Hemlock sightings, as recently as 2025, confirm it continues to spread across the Upper Midwest, including southeastern Minnesota. (2025 map courtesy EDDMapS, a web-based mapping system for documenting invasive species and pest distribution based at the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia)

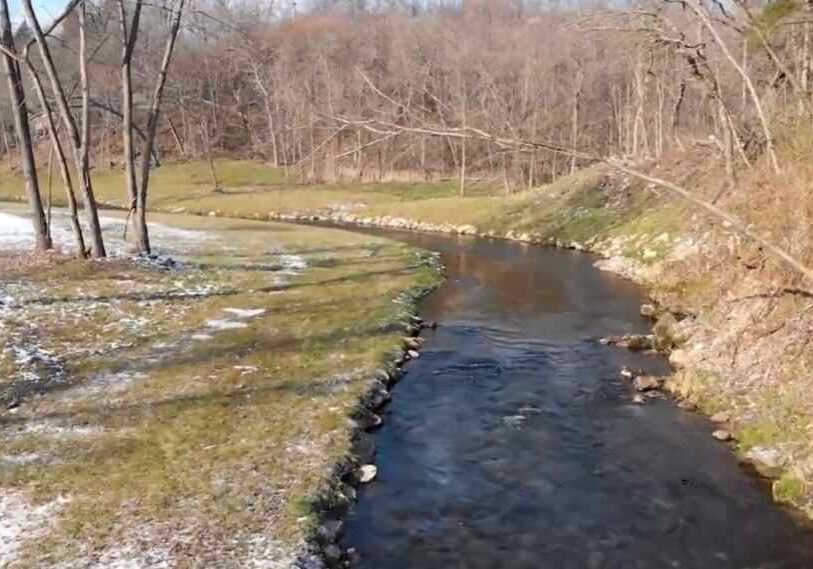

Mark Leoschke, a botanist with the Iowa Department of Natural Resources’ Wildlife Bureau, said poison hemlock likes moist soils and benefits from “disturbed areas,” like roadside ditches, flood plains and creeks or rivers, where running water can carry seeds downstream.

“It just benefits from periodic disturbance, and it is the way it can grow and maintain itself,” Leoschke said.

Anderson said the plant also favors areas along fences, and margins between fields and woodlands.

Generally, the plant isn’t a threat to lawns and residential yards, Leoschke said, because lawns are typically mowed regularly, which keeps the plant from maturing.

As indicated in this map, the density of poison hemlock in Southeast Minnesota is greatest in Fillmore, Olmsted and Wabasha counties, followed by Houston and Winona counties adjacent to the Mississippi River. (2025 map courtesy EDDMapS, a web-based mapping system for documenting invasive species and pest distribution based at the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia)

A ‘highly toxic’ plant

Poison hemlock — which is known by its scientific name conium maculatum and is native to Europe and Western Asia — starts growing in the springtime and is a dangerous plant.

“The most serious risk with poison hemlock is ingesting it,” Anderson said. “The plant is highly toxic and could be fatal to humans and livestock if consumed.”

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service, every part of the plant — from its stem to its leaves, as well as the fruit and root — is poisonous.

The leaves are especially potent in the spring, up to the time the plant flowers.

The toxic compounds found in the plant can cause respiratory failure and disrupt the body’s nervous and cardiovascular systems.

Anderson said it is possible for the toxins in poison hemlock to be absorbed through the skin, too.

“Some of the population could also experience dermatitis from coming in contact with the plant, so covering your skin and wearing eye protection when removing the plant is important,” she said.

Small white flowers are clustered in umbels 3-6 inches in diameter at the tips of the branches; plants bloom May-August but are most obvious in the first half of the summer. (Source: MN Dept. of Agriculture; photo by Robert Dane Banner)

Poison hemlock can also be fatal if consumed by livestock.

According to USDA, cattle that eat between 300 to 500 grams or sheep that ingest between 100 and 500 grams of hemlock – less than a can of beans – can be poisoned.

Though animals tend to stay away from poison hemlock, they may eat it if other forage is scarce or if it gets into hay. Animals that ingest it can die from respiratory paralysis in two to three hours.

Jean Wiedenheft, director of land stewardship for the Indian Creek Nature Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa said no one should eat anything from the wild unless they know exactly what they are ingesting.

The carrot family of plants, which includes poison hemlock, can be particularly treacherous. Water hemlock, a relative of the poison hemlock native to the U.S., is also toxic.

Giant hogweed, another member of the carrot family, can grow up to 15 feet tall with leaves that span two to three feet. Marsh said that if a human gets sap from the plant on their skin then goes into the sun, it can cause third-degree burns.

On the other hand, wild carrot, another invasive also known as Queen Anne’s Lace that looks similar, is generally considered safe or mildly toxic.

Poison hemlock has been found in over 300 locations in Fillmore, Houston, Winona and Olmsted counties in recent years, mostly along wetlands and streams, in ditches and along fields. What makes hemlock such a threat is that all parts of the plant contain neurotoxins that pose a danger to humans and animals — and can be fatal if ingested. Minnesota officials encourage anyone who believes they have seen poison hemlock to report it to local county agricultural inspectors. Additional information about poison hemlock in Minnesota can be found online from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and the Minnesota Department of Agriculture. Interactive maps providing details of specific sightings, density and more can be found on the EDDMaps site managed by the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at the University of Georgia.Poison Hemlock in Southeast Minnesota

Managing the plant

Poison hemlock is a biennial plant, which means it takes two years to complete its life cycle.

Removal strategies vary depending on where in the life cycle the plants are, where the plants are located, how abundant they are, what time of year it is and the ability of the person trying to manage the plant.

For example, Anderson said flowering plants generally need to be cut out and disposed of as trash. However, Anderson said that using herbicides on the hemlock when the plant is growing close to the ground in its first year is often more efficient and more effective in eradicating the plant.

In some situations, mowing can be an effective option to manage isolated infestations of poison hemlock as well, she said.

“Since (they’re) a biennial species, if we remove plants prior to producing seed, we can eliminate the possibility of new plants or increasing populations of these plants,” Anderson said. “Any location with poison hemlock will need to be monitored for several years.”

Successful hemlock management comes back to prevention.

“We often talk about the species (in the summer) because the white flowers atop the tall stems are very obvious on the landscape, but the species exists for the rest of the year as a relatively unassuming rosette of leaves on the ground that people don’t think of until they see the flowers, when it is too late for most effective management strategies,” Anderson said. “Every time a plant is allowed to produce seed, it adds to the soil seed bank and creates more future management challenges.”

This story is a product of the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, an independent reporting network based at the University of Missouri in partnership with Report for America, with major funding from the Walton Family Foundation.

Story edited for Root River Current by John Gaddo.