Youth Sex Trafficking Focus of League of Women Voters’ Public Forum

RUSHFORD — Youth sex trafficking is not unique to metropolitan Minnesota – it’s present in cities and towns of all sizes, urban and rural, including communities in southeast Minnesota.

That was the message delivered during a recent public forum led by Beth Holger, CEO of Minneapolis-based non-profit The Link; the event was hosted by The League of Women Voters of Fillmore County (LWV).

The audience of about 20, mostly women, were gathered in the Rushford-Peterson Schools Forum Room, a space that felt reminiscent of a small college lecture hall. They were there to learn about the realities surrounding youth sex trafficking, homelessness and other related issues.

Holger took the floor in a bright blue t-shirt printed with The Link’s logo; her mother beamed in the audience throughout the duration of her presentation (Holger shared later that Rushford-Peterson feels like home to her as she had grown up partially in the area). She was welcomed by Jo Anne Agrimson, Co-President of Fillmore County LWV, who explained that ‘equality of opportunity for education, employment and housing’ is among the League’s main objectives as a non-partisan organization.

When Agrimson introduced Holger as The Link’s CEO of ten and a half years – stating that the CEO’s intention is to eventually eliminate the necessity of her position – Holger nodded fervently.

What is the link?

With 270+ units of housing, The Link is the largest provider of housing for youth in Minnesota. Based in North Minneapolis, its programs have now expanded to all the suburban counties adjacent to the city. The organization employs between 180-190 staff members, as well as 42 youth. Holger showed a video providing an overview of The Link, in which she reiterates the fact that their “biggest goal is to truly work ourselves out of existence”.

Holger explained how The Link works to “support youth to have equitable access”, through five programs working with young people involved in juvenile crime and three youth advisory boards. The youth advisory board is a paid part-time position for youth who have experience in the matters on which they are advising. Their responsibilities include co-designing all of the programs, undergoing evaluations of the program twice a year, strategic planning, and sitting in on interviews.

Holger’s demeanor throughout the event was warm and open, her presentation peppered with jokes. She explained that she does this work because she has a loving family that is able to raise and care for her well, and not everybody has the same.

Holger doesn’t like the way youth are often portrayed by the media as people who get involved in crimes, frequently showing them as just lazy, bad, or troublemakers. Usually, she pointed out, there is something else going on. She wants to operate from the basis of looking at everybody she works with as an amazing person who has other challenges going on in their lives, helping them to identify their goals, and working with them holistically.

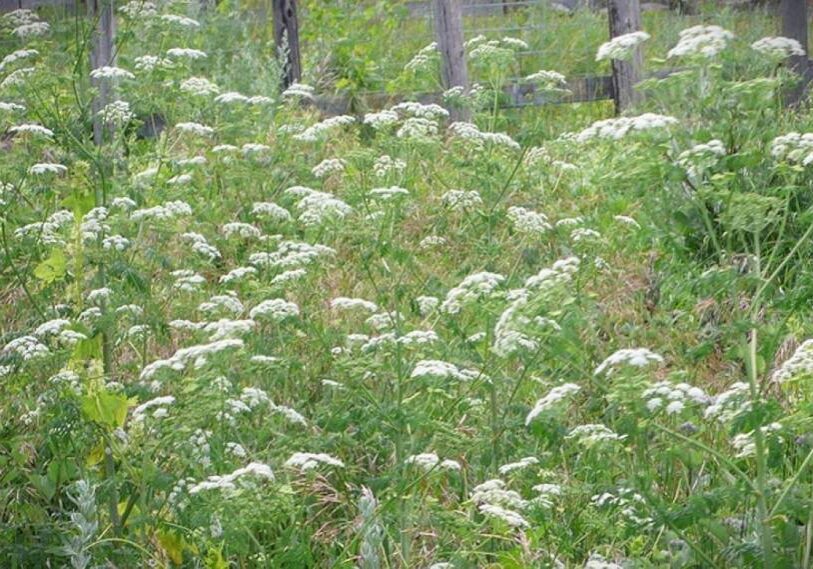

The Link handouts shared at the event. (Photo by Ella Deutchman)

Youth homelessness in Minnesota | Definition and causes

Minnesota has an estimated 4,782 unaccompanied youth experiencing homelessness. A “homeless youth” is defined by Minnesota statutes as “a person 24 years of age or younger who is unaccompanied by a parent or guardian and is without shelter where appropriate care and supervision are available, whose parent or legal guardian is unable or unwilling to provide shelter and care, or who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.”

Several key causes tend to result in youth homelessness. They include: severe family conflict resulting in the youth being kicked out of the home; a parent or guardian that is unable to provide care; parents or guardians who are also homeless; insufficient space in parent or guardians’ housing; a parent or guardian who is incarcerated or institutionalized; a parent or guardian who has died; a youth who has “aged out” or fell through the cracks of the child welfare, mental health, or juvenile justice systems; or youth who have been kicked out or disowned due to sexual orientation or gender identity.

Life is risky as a homeless youth

Young people living in this situation face above average risk factors for common societal problems. They are at higher risk for sexual exploitation (17% of homeless youth will be sexually exploited); higher risk for engaging in criminal activity or being victims of crime; higher risk of depression, PTSD, or other mental health struggle (54% of homeless youth); higher risk for suicidal thoughts (34%), and suicide attempts (24%); and higher risk for physical and sexual assault.

In addition, they tend to have difficulty finding legitimate and sustained employment and struggle to make it to school consistently. Typically, homeless youth receive insufficient healthcare and are also at a higher risk of STDs and pregnancy. Given Minnesota’s severe winter, all these hardships are exacerbated by intense cold.

Despite comprising only 26% of Minnesota’s metro area population, 73% of its homeless youth are BIPOC individuals. Additionally, Holger explained that a commonly held misconception, that Minnesota’s homeless youth are not Minnesotans, is factually untrue. The vast majority of our homeless youth are in fact Minnesotans themselves, not individuals coming over from other states.

After sharing these overviews of youth homelessness with us, Holger quipped, “I can never remember where I put my keys, but I can always remember stats about youth homelessness”.

Working to end youth homelessness

A range of homeless youth services is working towards the elimination of youth homelessness. These include street outreach programs, drop-in centers, homeless prevention programs, emergency shelters, host homes, rapid rehousing, transitional housing, and permanent supportive housing.

Minnesota’s Homeless Youth Act, in the works since 1999, includes an inclusive definition of what it means to be a youth or a young family, lessening limitations on who can receive aid.

The Act provides funding for the full continuum of services needed, while also allowing for innovation, culturally specific services, and flexibility. Holger added that this component is key, as it keeps different organizations, all with the same end goal in mind. In 2023, the Act’s funding received an historic increase in funding from $11 million dollars to $41.5 million.

Sex exploitation and trafficking

At least 5,000 students in Minnesota have traded sex, although this number is thought to be drastically underreported. Of those youth who have spent time in a juvenile correction setting, 12% have experienced exploitation or trafficking.

Factors that increase the risk of youth sex exploitation including homelessness, running away, being in foster care, being Black, Indigenous-American, or LGBTQIA, and youth with a prior history of sexual abuse.

Sex exploitation and trafficking can happen through familial pimping, peer recruitment, online recruitment, an individual posing as a potential boyfriend or girlfriend, or somebody enticing youth into modeling or other jobs that end up being a trafficking or exploitative situation.

Rules of the game

Holger said that youth victims of sex exploitation and trafficking tend to have their own vernacular for discussing their experience. One of these is referring to it as “the game”, or “the life”. Youth involved with The Link compiled some of the “rules of the game”. These include:

The forum was hosted by the Fillmore County League of Women Voters. Handouts and materials for participants were available at the event. (Photo by Ella Deutchman)

- Constant need to lie about one’s age

- All of your identification taken from you

- Needing to change your name

- Threats against family

- Always moving

- Repeated rape

- Beaten when money made is deemed insufficient

- Having to give your money away

- Needing to completely change your appearance

- Being tattooed on the neck with your abuser’s name

- Constant threat of violence

- Stuck in a situation of abuse

- Living with people who you call “family”, although these are people you cannot rely on

Red flags

Holger shared a variety of factors that could indicate a youth is experiencing sex exploitation or trafficking, especially when combined. These include facts not lining up, lack of ID, signs of a dominating or controlling relationship, substantial change in appearance, no control of their own finances, speaking in slang or lingo from “the life”, indicators of sexual or physical violence, romantic or sexual interest expressed in older adults, truancy or tardiness from school, anxiety, depression, fear, nervousness, tension, submission, hyper-vigilance, paranoid behavior.

Holger added that this paranoia can commonly manifest as a constant need to check one’s phone, coupled with high anxiety.

Minnesota Safe Harbor Law

The Link wrote Minnesota’s Safe Harbor Law, an instrumental and vital step that decriminalized “prostitution” offenses for youth under the age of 16. It has since been brought up to 18. The law also added the definition of sex trafficking into the child protection code, as well as increasing penalties for buyers.

The Link is currently advocating for the decriminalization of “prostitution” for all ages. “You are still a victim, even if you’re 45 and being trafficked,” Holger said.

Youth homelessness and sex trafficking in rural communities

These crises don’t always occur in larger metropolitan areas, and Holger shared that youth homelessness and sex trafficking takes places in rural communities too.

Talking with Holger following the event, she said she has worked with victims from southeastern Minnesota, including a victim who was sexually abused and groomed by her mother’s boyfriend. This resulted in other traffickers recruiting her into sexual exploitation, taking her to various private parties throughout Minnesota.

The public tends to think of traffickers as operating out of hotels, which is definitely prevalent, but traffickers will also come to private parties in an attempt to do business, events such as birthday or bachelor parties.

What can you do

If you believe someone is being sexually exploited or trafficked, there are some best practices to keep in mind.

First of all, do your best to stay calm. Do not act from a “rescue” mentality and instead work to be trauma-informed and non-judgmental in your response, actively listening to what the person has to say.

Be a validating presence, don’t contradict facts or information that is being shared with you. Don’t insist that the victim share information about their experience if they do not feel comfortable doing so.

Protect the confidentiality of the victim. Holger said that this is particularly vital in rural areas, where communities tend to be small and tight knit.

Finally, reach out to your local regional navigator, whose contact information you can find through the Minnesota Department of Health.

Additionally, The Link’s Safe Harbor Regional Navigator phone line is open 24/7, at 612-232-5428.

We all can be a part of dismantling misconceptions about, and working towards the end of, youth homelessness, sex exploitation, and trafficking. Some ideas from Holger about how we can work towards these ends include attending educational forums, volunteering or going on a tour, or finding other ways to bring increased awareness to the issue.

Narrative shift

Holger emphasized that in order to change the narrative around sex exploitation and trafficking, we need to talk about it in blunt and clear terms.

These survivors of exploitation and trafficking are victims, not criminals. Would a fourteen-year-old really choose of their own volition to have sex with someone several decades their senior? These youth are not delinquents or temptresses, they are children, coerced into making choices they would never make for themselves.

And still, as Holger makes a point to underline her presentation, youth experiencing exploitation and homelessness are profoundly resilient. These survivors are working today for The Link, beginning small businesses, working at Target, starting families. They are social workers, artists, musicians, and entrepreneurs.

The earlier we can reach youth, Holger said, the less trauma and harm has been done – and she reiterates the fact that “these youth are amazing once they find safety and someone to believe in them.”