Exterior view of the Fillmore County Poor Farm circa 1900. This structure was built in 1896, following the destruction of the original home by fire. This home was erected to house the county poor, some of whom are seated on the lawn and steps. (Photo courtesy of Fillmore County Historical Society)

Before Social Security, Fillmore County Poor Farm Helped The Poor And Aging

Editors’ note: Social Security – its benefits, financial challenges, long-term sustainability and possible reform – is on policymakers’ agenda again this year. Its history dates back to the 1930s when Congress enacted the Social Security Act in part to address poverty and aging issues during the Great Depression. Prior to this time, ‘poor farms’ were one approach to helping the country’s aging population.

AMHERST & CANTON TOWNSHIPS, FILLMORE COUNTY — The Fillmore County Poor Farm, outside the small village of Henrytown, was part of a statewide initiative in the late 1800s to provide housing for poor and elderly people.

At its start in 1868 it was considered one of the best of Minnesota’s county poor farms, but it eventually fell victim to a lack of funds and resources.

Its Beginnings

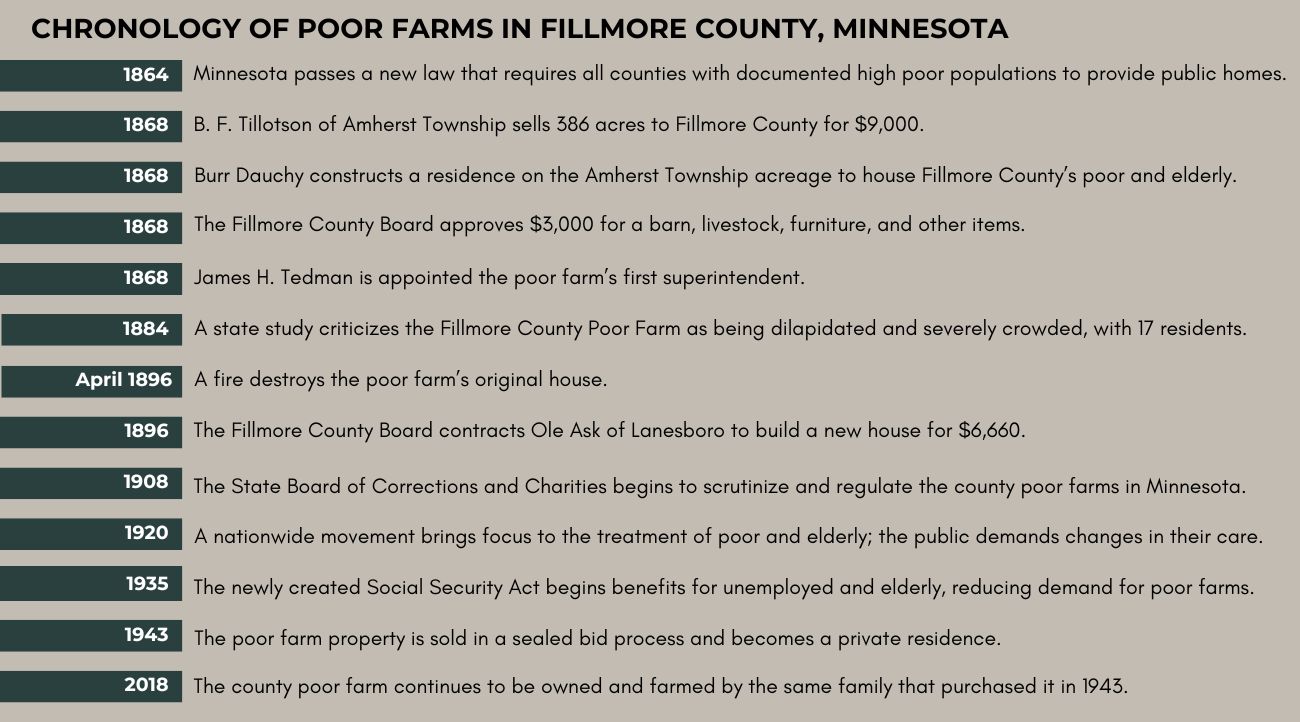

In 1864, a new Minnesota law required that all counties with a “significant” number of poor and aging people provide them with a home, daily meals, clothing, and medical care.

By this time, the county poorhouses in Eastern states—the first organized system of poor relief in the US—had already developed into poor farms. These institutions, the designers of the new system believed, would generate enough income to cover their own upkeep and perhaps even provide extra money for their counties.

The poor-farm system depended on finding good farmland, and Fillmore County was especially fertile.

In 1868, four years after the passage of the Minnesota law requiring counties to provide housing for the poor, the Fillmore County Board settled on a site for a farm. It purchased 386 acres in Amherst and Canton Townships from B. F. Tillotson for $9,000.

Burr Dauchy was hired to build the two-and-a-half-story house in July. The cost was $2,625. A barn and additional outside buildings were constructed. The board also approved $3,000 for the purchase of household furnishings and livestock.

The poor farm was ready for its residents in the fall of 1868, less than a year after planning had begun.

Its first superintendent, James H. Tedman, served in the position for two years. In its mention of the farm, the 1882 History of Fillmore County describes it as a well-managed 275-acre parcel of cropland, its main crop being corn, with several horses, cattle and hogs.

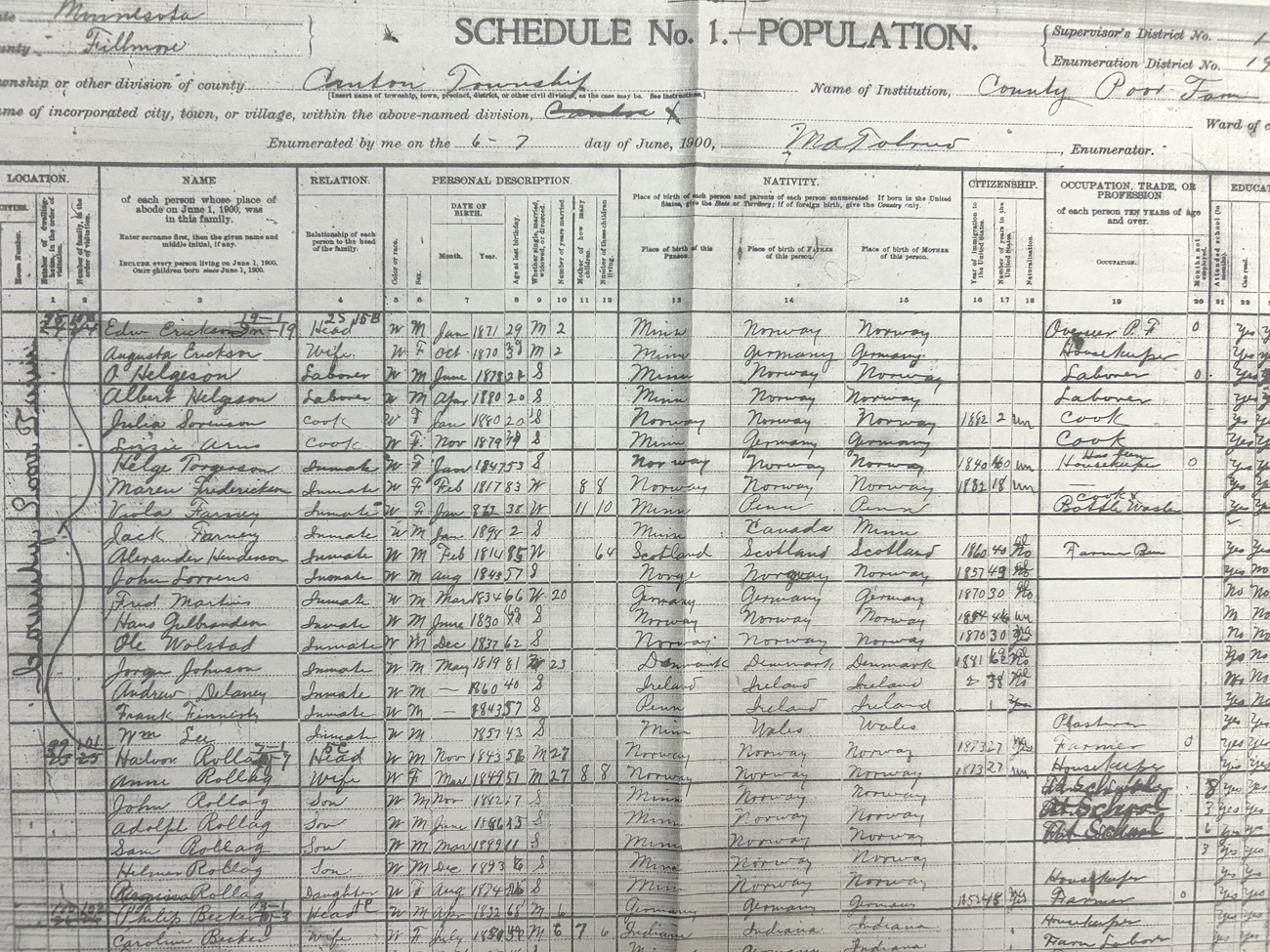

The 1900 Census lists the residents at the Fillmore County Poor Farm. Most of them were born in Europe. (Image courtesy of Fillmore County Historical Society)

Overcrowded and Underfunded

Seventeen people called the Fillmore County Poor Farm ‘home’ by July 1884. This small-sounding population, however, had stressed it beyond its capacity (twelve residents).

The Reverend Hastings Hornell Hart, secretary to the State Board of Corrections and Charities, criticized it as being underfunded, dilapidated, and overcrowded only sixteen years after it opened its doors.

A statewide study conducted by Hart found that women, men, children, elders, and mentally ill people often roomed together in poor farms, and that Fillmore County’s was no exception.

The board’s secretary, H. R. Wells, reported that nine people had shared a badly insulated sixteen-by-sixteen-foot room at the Fillmore County Poor Farm through the winter of 1884–1885.

In general, Hart found that few residents could contribute labor to their farm’s operation, as was originally intended. Larger houses with more bedrooms, bigger community spaces, and modern conveniences were needed. Funds, however, were not easily accessible.

Fire — And a New Beginning

On April 14, 1896, over a decade after Hart’s in-depth and critical report, the Fillmore County Poor Farm’s house was destroyed by fire. The County Board allocated $6,660 for a new house and awarded a contract to builder Ole Ask of Lanesboro.

Ask built a three-story, thirty-room house with a limestone basement. The building had wide hallways, an open staircase, and a walk-up attic with living space.

The 1912 History of Fillmore County, Minnesota described the house as “large, sanitary and commodious, steam-heated and furnished with running water and other conveniences. The barns are large and well kept.”

Author Edith McClure mentions in More Than a Roof: The Development of Minnesota Poor Farms and Homes for the Aged that it was “a first-class farm…quite a showcase.”

(Chronology provided by Minnesota Historical Society)

In 1902, the State Board of Corrections and Charities dissolved. A new board was created to continue oversight of poor farms, and Louis G. Foley was hired in 1908 to lead it. Foley approved new regulations for the farms’ management and operation, placing them under stricter state scrutiny.

By 1929, a nationwide movement created public demand for changes to the treatment and care of the poor and elderly.

A new Federal Social Security Act of 1935 was the death knell for the county poor farms. The act gave assistance to poor and elderly people living in privately owned institutions; as a result, public poor farms lost residents to these newer homes and started to close their doors.

By 1950, the Fillmore County Poor Farm was privately owned and used as a single-family home. The same family has owned the property since purchasing it from the county in 1943 in a sealed bid process.

…………………

Contributor

Author Amy Jo Hahn’s historical work includes several published articles, an oral history project titled Voices of Harmony, various archival projects, research, and content contribution to PBS-station KSMQ’s “R Town” historical segment. She is the author of Lost Rochester (Arcadia Publishing, 2017). Hahn holds a BA and an MA in mass communication, and a certificate in historic preservation. Her hometown is Harmony; she resides in Rochester.

This article was published in 2018 in MNopedia, an online encyclopedia about Minnesota developed by the Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) and its partners. It is a free, curated and authoritative resource about Minnesota. Its articles are prepared by historians, consulting experts, professional writers and others who have been vetted by MNHS.

This article was reprinted with permission of the author. All rights reserved.