Kate Glor, life enrichment director at Chatfield's Chosen Valley Care Center, unloads some supplies during an emergency drill to prepare Fillmore County Public Health, area emergency personnel and local care providers for potential emergency situations. (Photo provided by Fillmore County Public Health)

Area Public Health Officials Remain Vigilant At All Times

PRESTON — In 2000, when Brenda Pohlman started her career with Fillmore County Public Health (FCPH), the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the United States had eradicated measles due to the success of its vaccination measures. In the 25 years since then, no cases of measles have been recorded in Fillmore County.

Pohlman would like to see those positive trends extend much further into the 21st century, but she sees trends that raise doubts. A recent measles outbreak in Texas, New Mexico and now Oklahoma has infected hundreds, led to severe hospitalizations and caused two deaths. Smaller outbreaks are starting to show up in other states.

Additionally, Minnesota Department of Health data shows Fillmore County residents are below the state average in vaccination rates — a level that is declining each year and one that is well below the level desired of herd immunity to buffer a population from a measles outbreak.

Although a measles outbreak in Fillmore County isn’t imminent, imagining horrible things that can happen to local residents is what Pohlman does. In fact, it’s part of her job description.

While her official title is public health educator, Pohlman has a variety of duties, including emergency preparedness and response, which covers situations ranging from natural disasters to disease outbreaks. In this role, she imagines “worst-case scenarios” for Fillmore County and makes health-related plans to cope with unexpected disasters.

Pandemic response included community support

Pohlman has been involved in several emergency responses, such as the Rushford flood in 2007 and the outbreak of H1N1, sometimes called the swine flu, in 2009, as well as tornadoes, power outages and even a cyberattack. However, the Covid-19 pandemic that started in March 2020 was by far the most extensive response for her department.

Pohlman and staff at FCPH started having conversations about a potential pandemic in November 2019, well before most people had even heard the term covid and four months before the official declaration of a pandemic by WHO.

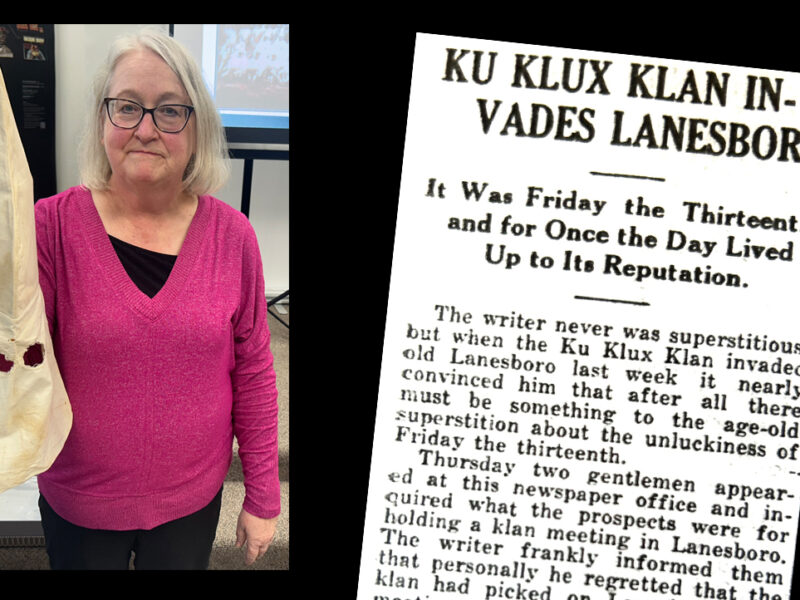

Fillmore County Public Health received a lot of local support for its efforts during the pandemic. In addition to cards and balloons delivered to the staff, this gown, made up of many of the items used by the department during the pandemic, was presented to Fillmore County by the Ladybug Brigade, a group of local residents who volunteered to make masks and gowns. (Photo provided by Fillmore County Public Health)

“We had already had inklings something was happening, and we were preparing,” she said.

FCPH created seven different teams or task forces to protect local residents during the pandemic, including things such as collecting resources and supplies, providing or arranging for transportation, and even testing people. Not all of the units were needed, but they were formed to cover all scenarios.

The department had assistance from entities such as the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) and the Southeast Minnesota Disaster Health Coalition, in which counties support each other to cover shortages in resources and share in preparedness. But it also saw local residents pitch in to help.

Many local volunteers were willing to sew masks and gowns. Other volunteers cut out gowns and others donated fabric. That effort resulted in thousands of kits that FCPH was able to send to daycares, schools and long-term care facilities.

“We had some amazing folks, so many wonderful people who were willing to donate time, and masks,” said Pohlman.

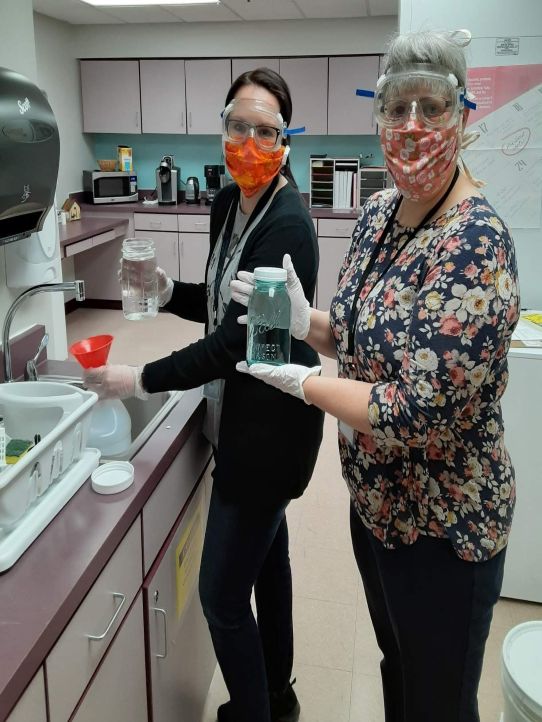

Local businesses also helped. Hand sanitizer was in short supply then, but the POET ethanol plant in Preston and Harmony Spirits, a craft distillery, used their operations to make hand sanitizer for the county.

“At that time, it was really hard to find containers to put it in, so we used Mason jars, and it looked like we had a lot of moonshine,” she joked.

The department became responsible for case investigations and contact tracing after the MDH became overwhelmed with the volume of cases in Minnesota. Local staff detected several local outbreaks and discovered how far and fast the disease was able to spread. For example, one case showed one or two people infected more than 75 people.

When vaccines became available, the county department booted up a vaccine unit in the lower level of the county building in Preston. Everyone on staff assisted with vaccinations, which wasn’t the case with other health departments in Minnesota.

Public Health staff bottled hand sanitizer for long-term care facilities during the Covid-19 pandemic. Sanitizer for the county department came from the POET ethanol plant in Preston and Harmony Spirits. (Photo provided by Fillmore County Public Health)

“I was very proud of the work we did around a couple of things for the size of the health department we are and the number of nurses that can actually put shots into arms, how many people were vaccinated,” said Pohlman. “We gave thousands of vaccines.”

The investigation and enforcement unit didn’t do a lot of enforcement, instead using a more consultative or educational approach by giving organizers of potential large group events information on how to comply, noted Pohlman. Although the rules regarding covid caused many tensions across the United States, things went fairly smoothly in Fillmore County.

“I think our community was very supportive,” said Pohlman. “I know that there were people who disagreed, but there were very few people who were vocal to us and disrespectful to us. I thank the Fillmore County people for always being respectful even if they didn’t always agree. I appreciate that. Our department does too.”

Nurse Paula Melver gives the first Fillmore County Public Health Covid-19 vaccination to a first responder during the pandemic. (Photo provided by Fillmore County Public Health)

Measles now a concern

Now that covid is out of the emergency pandemic phase, other concerns have risen to prominence. A primary one is the disease Pohlman has never seen in Fillmore County during her time in public health: Measles.

While the pandemic showed various local residents stepping up to support the emergency effort, diseases such as measles take mass unity to protect residents of the county. Currently, county residents are slipping in efforts to protect each other due to falling rates of vaccinations.

“We are continually looking at where our risks are. In Fillmore County, we have some vaccine hesitancy,” Pohlman said.

Only 71 percent of 2-year-olds in Fillmore County have started the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine, according to October 2024 data from the MDH. The state average is 76 percent, which is still well below the state goal of 90 percent. True herd immunity is generally considered even higher at 95 percent.

A total of 79 percent of adolescents in the county have received the MMR vaccine, but that is also below the state average of 88 percent and the desired rate of 90 to 95 percent. The below average rates are the same for most other vaccinations, including polio and DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis), for youth as well as adults in the county.

“We don’t have, in some cases, a high enough level to protect the rest of the community that chooses, for whatever reason, not to be vaccinated,” said Pohlman. “Most of these vaccines are very, very effective, like 90+ percent or more effective, in stopping these infectious diseases.”

One reason for hesitancy can be lack of access, but Pohlman doesn’t think that is a problem in Fillmore County as there are plenty of options for transportation, hours of availability and programs to cover costs. The decline in vaccinations has been even greater since the pandemic, partly because routines were broken and people don’t remember or haven’t seen the devastating effects of past disease outbreaks, noted Pohlman. However, a bigger factor is likely the spread of misinformation about vaccines.

“There is no evidence to show that autism is caused by vaccines,” said Pohlman, yet some people have a hard time getting past the 1998 Wakefield study that purportedly found a link, even though that study has since been charged with fraud and conflict of interest. She said people need to understand how science works as there were just 12 children in that study compared to hundreds of thousands who get vaccines every year.

“I would ask for people to look for credible information,” said Pohlman. “What I mean by credible information is the big three — the Minnesota Department of Health, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization. Start there before diving into something that may or may not be scientific based, or evidence based. Or call us and ask us and we can certainly help people find information about any health-related topic.”

Vaccines not only help individuals, but also their neighbors as they prevent the spread of infectious diseases that can cause grave problems for people who can’t get vaccinated, such as infants. They help in a global sense as well.

“These routine vaccines are very important for managing illnesses we don’t want people to have, that they may not have seen and might think there is no threat, but there really is, like measles or something as simple as a flu vaccine because if we get people vaccinated each year it helps prevent that virus from mutating into something we can’t get vaccinated for,” said Pohlman.

Measles is particularly concerning because it is so contagious. Nine out of 10 unvaccinated people will become infected with measles if they come into contact with an infected individual, according to the CDC. Babies and young children whose immune systems are still developing are at higher risk of serious complications.

“The measles outbreak in Texas has taken a toll. Now there are associated fatalities with it,” Pohlman said. “For unvaccinated children specifically, the fatality rate is very high. Almost always children with measles get hospitalized and it’s not an in and out thing, it’s weeks of treatment.”

She noted that it is really hard to stop something like this from starting, especially if there are enough people who are hesitant to get vaccines. Most cases of measles originate from international travel since immunity isn’t as widespread in other countries. However, once started, the disease often spreads in the United States in areas with low levels of vaccinated residents.

Vaccinations aren’t the only way to stop the spread. People also need to take precautions if they are infected.

Other threats occasionally touch county

Just as many people may not be aware of the department’s responses to emergencies, they may also not realize how many threats have faced the county over the years.

So far in 2025, the county has identified nine cases of whooping cough, or pertussis, and one case of chicken pox that was diagnosed and several others of likely undiagnosed chicken pox either because people weren’t tested or they were tested outside the window for detection, noted Pohlman.

“It’s really important for us to have folks who think that something is going on to go in and get tested. It’s extremely important for…stopping the spread,” she said.

Fillmore County Public Health did a full-functional exercise in March with Chosen Valley Care Center, Chatfield, and Good Shepherd Lutheran Services, Rushford. Chosen Valley sent four mock evacuees to Good Shepherd — staff there then worked to find places for the evacuees at their facility. (Photo provided by Fillmore County Public Health)

No cases of active TB had shown up in Fillmore County in decades, but recently one was reported along with several people with latent TB, which means the TB isn’t active, but these people need to take medication to prevent it from turning into active TB.

In a related incident, a poultry farm in Fillmore County did a large animal cull along with a shutdown and mass cleaning because of the avian flu, noted Pohlman, who added that the department works with veterinarians in these cases to make sure the workers can get protective gear and regular flu vaccines.

Constant state of preparation

Fillmore County Public Health, which currently has 21 members, keeps abreast of trends and health research as it is in a “constant state of preparation and response,” said Pohlman.

“We’ve been a part of a lot of responses, whether we are visible or not,” she said. “Not every disaster requires a public health response, but there are many reasons why they do.”

State and federal grants help the department work on things such as preparedness and response, training of staff and equipment needs. Staff also participates in practice drills in conjunction with local agencies and facilities. For example, staff recently had an exercise around a diarrhea illness, which prepared it for mass dispensing of pills, not just vaccinations.

A March 2025 exercise involving two Fillmore County care centers — Chosen Valley Care Center in Chatfield and Good Shepherd Lutheran Services in Rushford — along with county emergency management, included an evacuation drill. Nursing homes have agreements with each other to share space if an event happens.

The county is also part of a health alert network, which includes a regional epidemiologist along with state and national resources to keep the local staff abreast of trends. In addition, Pohlman said she sees great local support because the county is small enough that there is constant communication among health providers.

Worst case just a plane ride away

Many areas don’t have the capacity to handle mass fatalities from this type of disease. For example, Fillmore County can handle up to 13 deaths a day. Anything beyond that requires outside resources, which may also be dealing with the same thing in other locations.

With global travel so prevalent, “I always think of it as one plane ride away,” she said, noting that a carrier may not have symptoms, leading to the disease spreading before it is even identified.

While the worst of the worst-case scenarios may make Pohlman cringe, she and the other staff at FCPH focus on trends more likely to affect local residents, whether they are global threats or isolated local events.

“You start to see something, you get to be vigilant of it, and I pay attention to those things because that’s part of what I do,” she said. “You know, like every time there is a storm, I look at risk, and where do we have people that might get flooded and what would we be doing if these people get flooded.”

While FCPH is constantly preparing for potential future emergencies, it also deals with the aftermath of emergencies long after they have faded from the memories of most people.

“Disaster response is a long process, a lot longer than a lot of people even think,” said Pohlman. “The community is ‘I’m done with this,’ but you still have the stuff that has to happen after that. We see the aftershocks of it for a long time.”

…………………

Contributor

David Phillips, of Spring Valley, had been a writer, photographer, editor and publisher with various newspapers for 45 years until he retired as publisher of the Bluff Country Newspaper Group in southeastern Minnesota in 2020.