Cattle move through a pasture in a rotational grazing operation. (Photo by Ann Wessel, BWSR)

Rotational Grazing: Pipeline To Water Quality And Soil Health

South Fork Root River benefits from converting expired CRP into productive pasture

NORWAY TOWNSHIP/FILLMORE COUNTY — The rotational grazing system Carter Lee installed on 70 acres of Fillmore County blufftops south of Rushford is revitalizing pastureland, improving soil health and protecting the Root River, a designated trout stream.

“That piece originally was in the CRP program (Conservation Reserve Program) and when it came out, we decided we would really like to put (the land) back into perennial grass to use for grazing,” Lee said.

The need for fencing and a reliable water source led Lee to work with Dean Thomas, a Fillmore Soil & Water Conservation District (SWCD) based regional grazing specialist and soil health technician. Together, they devised a plan that would support about 250 cow-calf pairs. The result: a 568-foot-deep well, a pumping station powered by electricity, and pipes that carry water to one 11,500-gallon grain bin sheet tank and four 1,300-gallon tire tanks. Nearly 3 miles of high-tensile fencing encloses the pasture and divides the paddocks.

Rochester-based USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) engineering technician Charlie Blackburn helped to design the water lines. Fillmore County-based NRCS District Conservationist Jessica Bronson and Fillmore SWCD Administrator Riley Buley secured funding.

Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) assistance from NRCS and Watershed-Based Implementation Funding (WBIF) from the Root River One Watershed, One Plan partnership supported the project.

“With big projects like this, EQIP alone would have covered maybe 40% and (that’s) not feasible. So that’s the benefit of having the One Watershed, One Plan money,” Thomas said. Together, EQIP and WBIF cover 90% of grazing systems’ cost. Landowners pay the balance. Lee did additional work on his own.

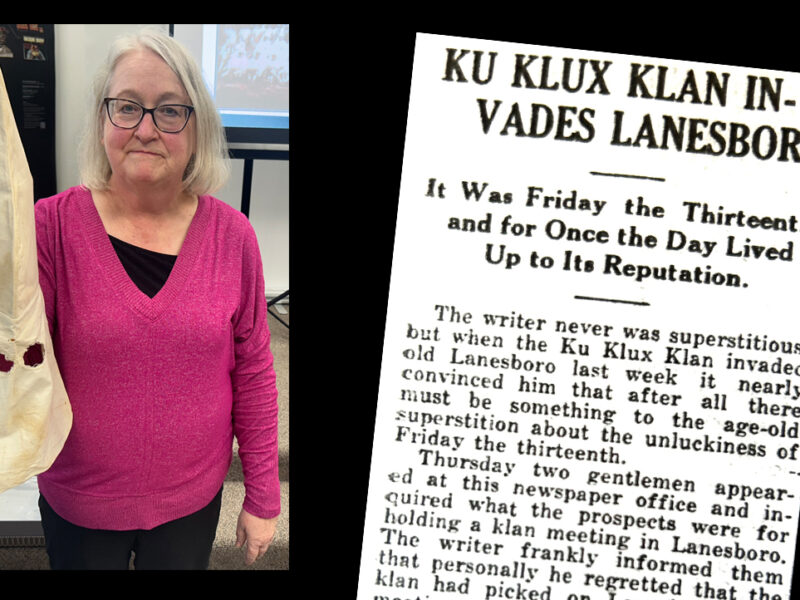

Fillmore SWCD-based regional grazing specialist Dean Thomas reviewed plans with landowner Carter Lee in September 2023. In fall 2024, Lee was working with Thomas on another EQIP-supported rotational grazing project that involved more than 14 miles of high-tensile perimeter and interior fencing. (Photo by Ann Wessel, BWSR)

Livestock not Row Crops

Thomas, who is now employed by the SE SWCD Technical Support Joint Powers Board (Technical Service Area 7), explained how rotational grazing aligns with watershed goals.

“If we don’t have cattle on the landscape it’s going to be row crops. And there’s a lot of land in southeastern Minnesota that shouldn’t have row crops — that should be in some kind of pasture or hay. The more we can manage the grasses we’ve got, maybe that’ll keep the cattle on the land and produce forage and also help with resource concerns,” Thomas said.

“If we’ve got cattle on the land, (by) managing the grasses we’re going to promote soil health, we’re going to promote water quality,” Thomas said.

Rotational grazing improves soil health by allowing regrowth and more well-developed root systems. Healthier plants pull in more nutrients and hold more water. Rotationally grazed animals distribute manure more evenly.

Deep roots and dense, perennial cover also curb wind and water erosion. That benefits water quality by helping to keep sediment and the pollutants it carries out of streams, rivers and lakes. The 70-acre site drains to the South Branch Root River, which eventually flows to the Mississippi River.

A sixth-generation farmer, Lee took over his grandparents’ operation about 10 years ago. Farming skipped a generation; Lee grew up in a Twin Cities suburb but spent summers working with his grandparents.

Over the years, he had expanded rotational grazing to other expiring CRP enrollments. On the home farm, which includes the 70-acre site, Lee aims to consolidate the herd and graze each pasture for a shorter time.

Rotationally grazed cattle drank from one of the 1,300-gallon tire tanks in September 2023 in Fillmore County. Getting a reliable water source to the site was key. Concrete pads protect the heavily used areas around the tanks. (Photo by Ann Wessel, BWSR)

The grain bin sheet tank provides the only water source for cattle grazing on grassland within the adjacent Choice State Wildlife Management Area (WMA). Lee worked with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources on an agreement where, in lieu of a lease, he inter-seeded a summer annual mix on the WMA. Each year, he’ll leave one-third of it ungrazed to feed over-wintering wildlife. He is swath-grazing the rest, turning the cattle out onto swaths of sorghum-sudangrass and pearl millet mowed just before the first big snowfall.

Low inputs equal profitability

Within the past few years, he has converted some corn and soybean fields to pastureland by planting summer annuals that can be grazed three or four times a season.

“It is a business, and it has to remain profitable. But I think we’re trying to do it with low inputs and being regenerative and trying to be mindful of conservation and the environment that we’re in,” Lee said. “It’s an ecosystem that involves a lot of creeks and the river. . . . We’re trying to preserve it and manage it in a way that is sustainable, both economically and from a conservation aspect.”

Seeding tillable acreage into pasture was a turning point.

“We started looking at things differently, not that we needed to farm everything, but we could still make a profit by grazing cattle on some of these acres that were maybe more prone to leaching pesticides or fertilizer into the river,” Lee said.

Dean Thomas Fillmore SWCD-based regional grazing specialist and soil health technician, put into perspective the size of a newly installed, 11,500-gallon grain bin sheet tank, which is the only water source for cattle grazing within the adjacent state wildlife management area. (Photo credit by Ann Wessel, BWSR)

Fall-seeded winter rye is grazed in the spring. Next, that land is seeded into a 10-species summer annual mix — including sorghum, millet, sunflowers and brassicas — that is grazed twice during the summer before being planted back to winter rye.

Elsewhere, Lee has planted pearl millet and sorghum-sudangrass in May to stockpile for winter swath-grazing. Early spring seeded oats and peas provide winter feed for feeder calves.

“We’re just trying to (orient) the acres that are not in permanent grass towards our livestock. It’s also reducing our need for commercial fertilizers, for pesticides and insecticides, which we’re pretty conscientious about in that area because of the South Fork of the (Root) River and other smaller tributaries. We’re trying to be sensitive to what we’re applying in and around those watersheds.”

The rotational grazing plan for this Fillmore County site required nearly 3 miles of high-tensile fencing to enclose the pasture and divide the paddocks. (Photo by Ann Wessel, BWSR)

In fall 2024, Lee was working with Thomas on another EQIP-supported rotational grazing project. It involved more than 14 miles of high-tensile perimeter and interior fencing; four wells, pumping plants and pressure tanks; nearly 1.3 mile of deep-buried pipeline and just over 2.5 miles of surface pipeline; three 11,500-gallon grain bin sheet tanks with concrete pads; four 5,200-gallon grain bin sheet tanks with concrete pads; four 1,300-gallon tire tanks and 11 1,000-gallon tire tanks with concrete pads; and 44 acres of brush management.

……………….

Contributor

Contributor

Ann Wessel is an Information Officer with the Minnesota Board of Water and Soil Resources whose mission is to work with partners to improve and protect Minnesota’s land and water resources.

USDA/Minnesota Natural Resources Conservation Service is an equal opportunity provider, employer and lender.

Watershed-Based Implementation Funding is funded solely by the Clean Water Fund. WBIF grants support watershed planning partnerships throughout Minnesota. The Clean Water Fund receives 33% of the sales tax revenue generated by the Legacy Amendment that voters passed in 2008 and recently renewed in the November 2024 general election.

![]()